Doveryai, no proveryai, a Russian proverb whose English translation Trust, But Verify made famous by the late President Ronald Reagan during negotiations with the Soviet Union has been a topic of debate ever since, not only in the realm of politics but also in many other aspects of wherever you think you might get tempted to use it. To help sort this out, Nan S. Russell in Psychology Today provides a context based usage approach that works just right.

When outcome is essential and matters more than relationship, use trust, but verify. When relationship matters more than any single outcome, don’t use it.

So true that. But since there are no relationships to care for when it comes to being a good steward of our money, we should trust little and verify a lot. And that task becomes a lot easier with a bit of intuition and access to data.

So there is this thing called rebalancing and it means exactly as it sounds. Say we start with a 60/40 stock-bond portfolio and over time as the markets evolve, that allocation drifts to say 65/35. If the intent is to maintain a constant allocation, we’d sell the stock component of the portfolio, taking out the excess and buy into the bond portion to bring the allocation back to 60/40. That’s rebalancing.

And it sounds like a great idea. We sell something that has gone up and buy the other that has gone down – a classic buy low, sell high approach. So that’s great. But then I read something along the lines that rebalancing between stocks and bonds works but rebalancing within a category is not ideal or does not work as effectively.

Take stocks as a category for example. You’ll likely own some large company stocks, mid-size company stocks and some small ones. And then you’ll own developed market international stocks and emerging market stocks and so on. Not all of them will move in the same direction all the time. Some will zig while others zag. Or some will zig some while others will zig more and so on. So if you rebalance within a category, you would be theoretically doing the same thing that you ideally would want to do – buy low and sell high.

But now there’s this doubt and we need to get to the bottom of it to make sure all’s okay. So as we would do and as we should do, we test both approaches at once to validate that what we’ve done all along was not inferior to what we should have done.

So we go back to data and test whether an invest & forget approach works better than say rebalancing annually. Ideally we would and should rebalance as often as there is an opportunity to rebalance but let’s just assume we do it once each year. We’ll use data on annual returns for four asset classes to test the two approaches.

- Large company U.S. stocks

- Small company U.S. stocks

- International stocks

- U.S. bonds

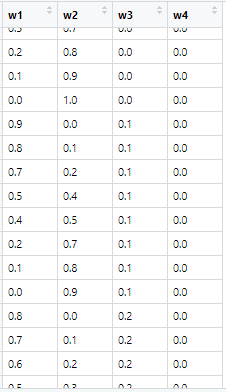

We invest $100 in a portfolio comprised of these four asset classes at the start of the entire time period in varying proportions of 10% increments and assess whether rebalancing does what it is supposed to do. A snapshot of different portfolio combinations is shown below.

Each row is one portfolio and with 10% incremental allocation spread across four asset classes means 258 different portfolio combinations we get to try this on.

Starting with year 1, in year 2 in case of the rebalancing approach, we sell whatever has deviated to the upside from the original allocation and buy what has declined to bring the allocation back in line. For the invest & forget approach, we split and invest the original $100 into the allocation we started out with and let the money ride till the end of the period. The end of the period by the way is 2018 and the dataset contains 49 years of data starting in 1970. So we are comparing the ending values of each portfolio at the end of 2018 to test the rebalancing vs. invest & forget approach.

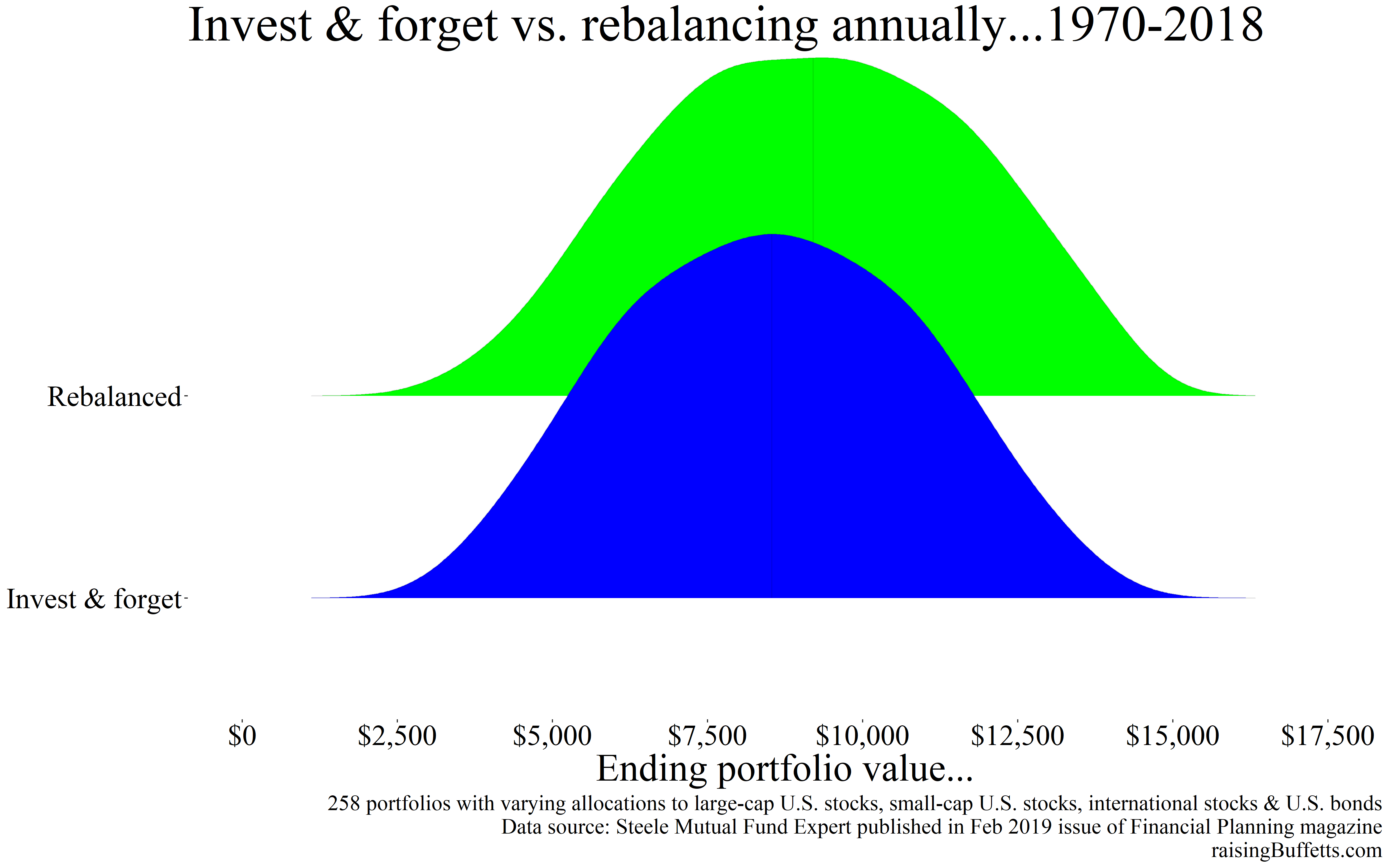

The first thing we should do to get a good feel is to look at how the ending values are distributed between the two options.

So clearly rebalancing works as is evident from a slight right shift of its distribution as compared to invest & forget. The spread is a bit wider though with rebalancing which is not desired but a bigger question is, are we comparing the same portfolios when comparing outcomes between the two? What we should ideally compare is the ending value of portfolio 1 in the invest & forget case with the ending value of portfolio 1 in the rebalanced case, the ending value of portfolio 2 in the invest & forget case with the ending value of portfolio 2 in the rebalanced case and so on.

So that’s what we have done next and this is what we find when we do a portfolio by portfolio comparison of the ending values…

- Out of 258 portfolios, each with a different asset allocation, the ending values of 243 portfolios that were annually rebalanced equaled or outperformed those of the invest & forget ones. So a 94% outperformance rate if the portfolios were rebalanced as compared to invest & forget.

- 79 portfolios out of 258 that were annually rebalanced outperformed invest & forget ones by more than 10%.

- And the ending values of three out of 258 portfolios outperformed invest & forget by more than 25%.

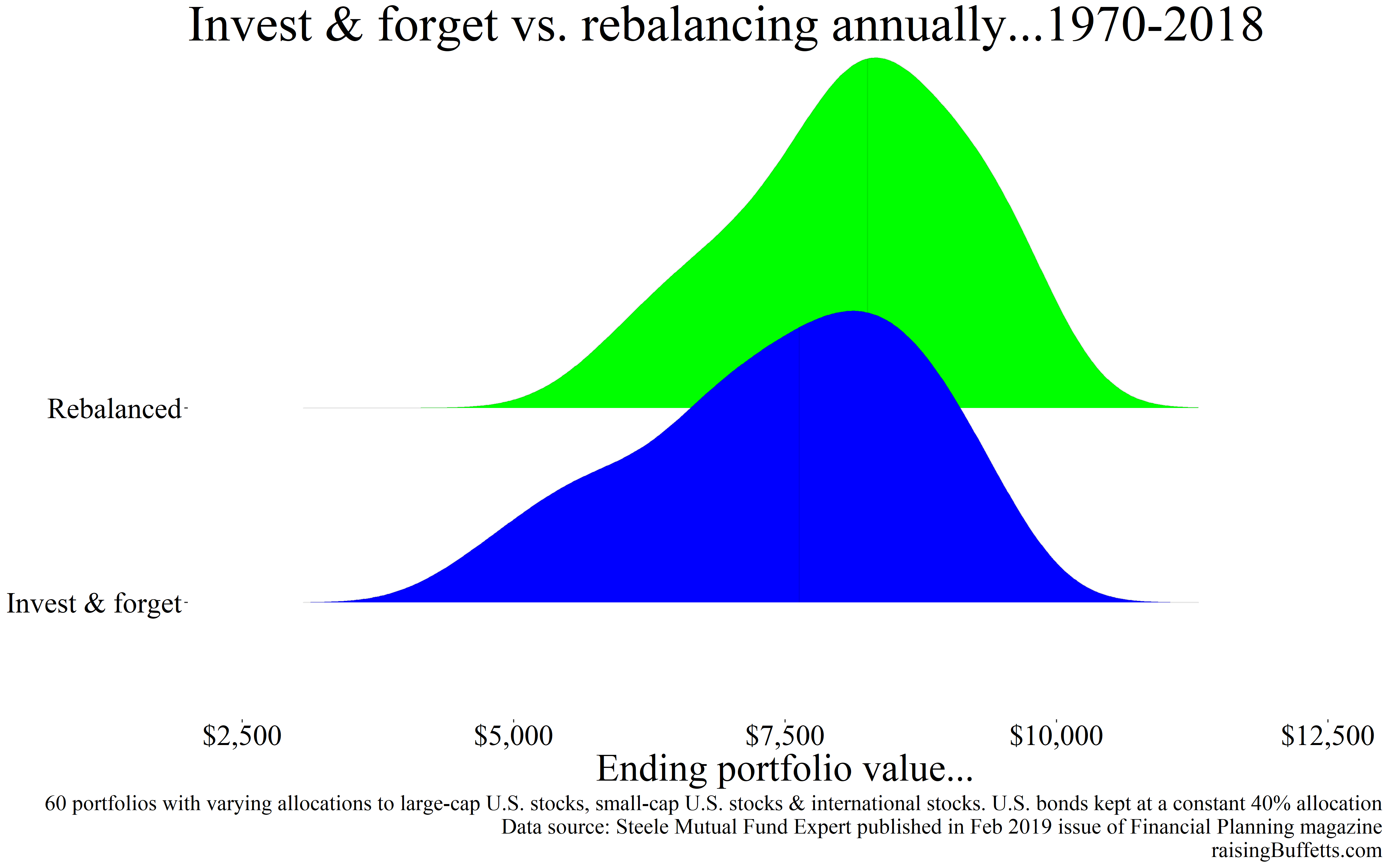

So rebalancing works or at least worked almost all the time. But what if the bond allocation was held constant at say 40%? The original thesis was that rebalancing is more effective between categories (stocks vs. bonds) versus within categories (within stocks or within bonds). So trying that out…

Apparently the same story here with the shift in distribution for the rebalanced case more to the right than for the invest & forget approach. Oh and by the way, because the bond allocation is held constant with only the remaining three asset classes in the stock category allowed to vary, only 60 portfolio combinations are possible.

A portfolio by portfolio comparison of the ending values yields the following results…

- Out of 60 possible portfolios, each with a different asset allocation and a fixed bond allocation, the ending values of 59 portfolios that were annually rebalanced equaled or outperformed those of the invest & forget ones. So a 98% hit rate making the case even stronger for the rebalancing approach.

- 25 portfolios out of 60 that were annually rebalanced outperformed invest & forget ones by more than 10%.

- And one outperformed invest & forget by more than 25%.

So if you had to wager, rebalancing still wins.

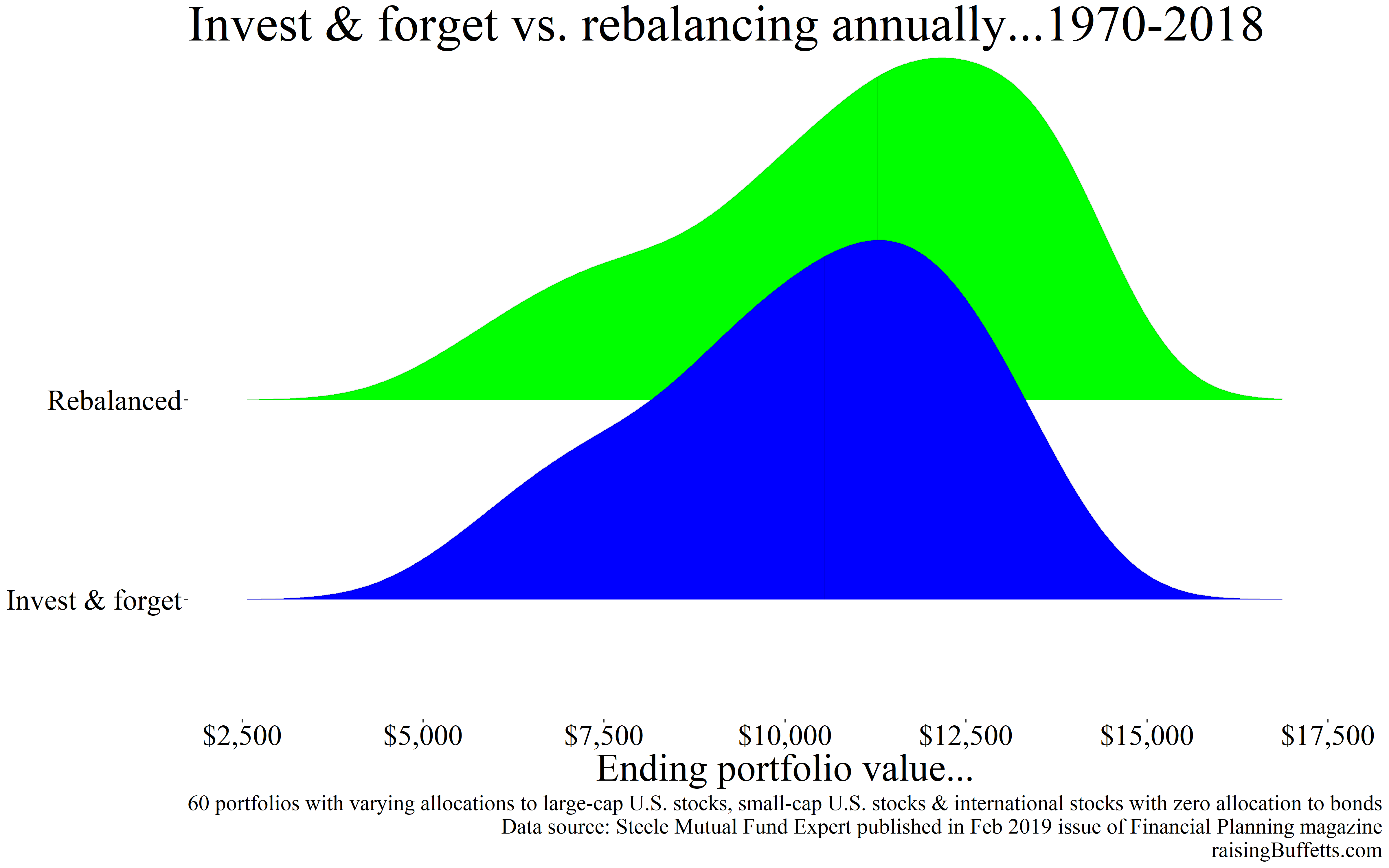

What if you owned an all-stock portfolio? Would rebalancing still outperform invest & forget?

Appears to be a yes. And again as before, only 60 portfolio combinations are possible so a portfolio by portfolio comparison yields the following…

- Out of 60 possible all-stock portfolios, the ending values with the rebalanced approach equaled or outperformed invest & forget each and every time. So a 100% hit rate in favor of rebalancing.

- But none of them outperformed by more than 10% so not a big thumping vote for one over the other.

But what if the returns of the past do not repeat in the same sequence? Could the outcomes be different with a different sequence of returns?

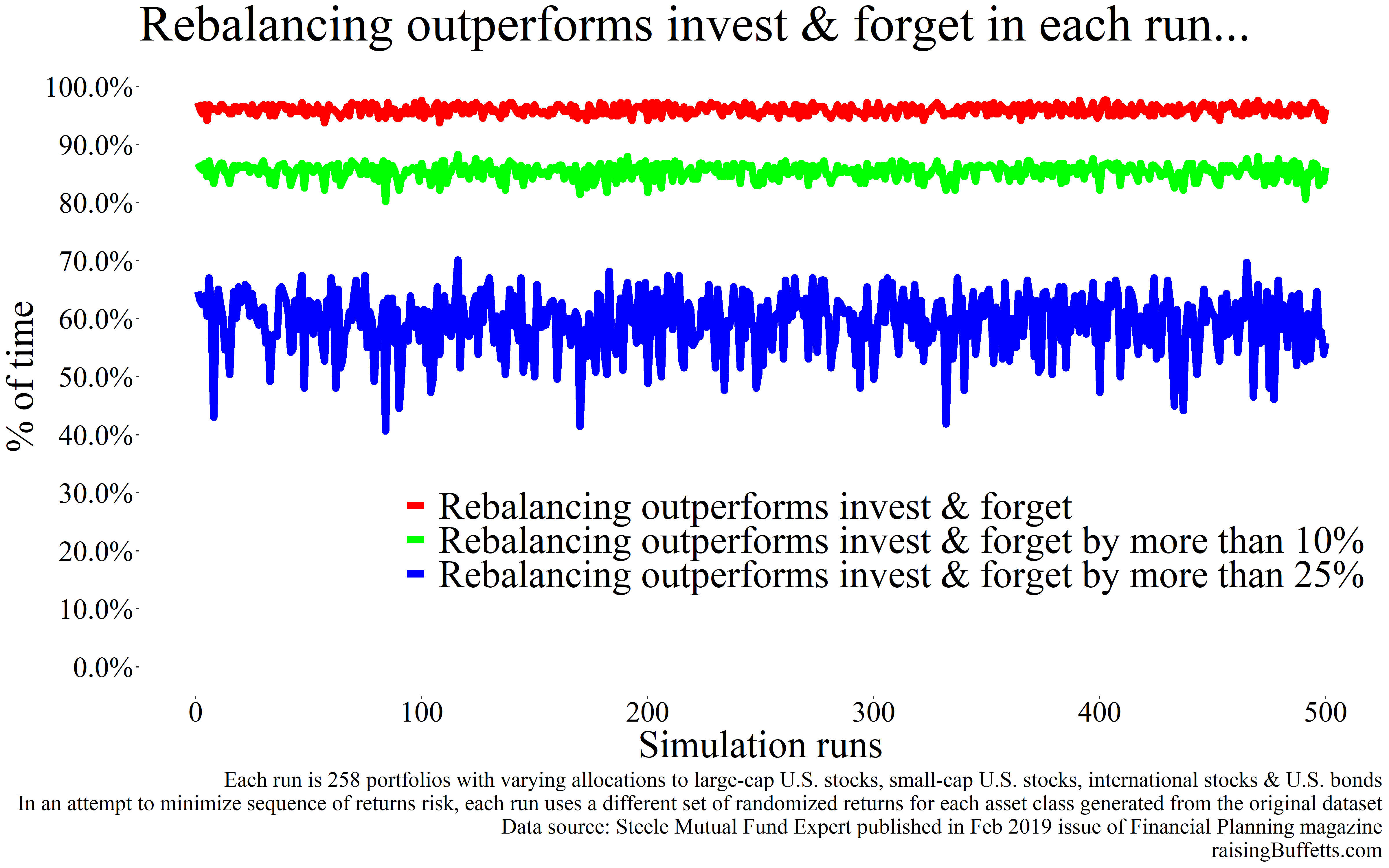

To assess that, we sample returns for each asset class randomly and recreate the asset class returns dataset each time and compare the ending portfolio values between the two approaches. And just to make sure that we have at least attempted to try every which way to convincingly make one approach fail over the other, we do this 500 times. The results…

With portfolios constructed out of a combination of the four asset classes (large company U.S. stocks, small company U.S. stocks, international stocks and U.S. bonds)…

So a very strong vote in favor of rebalancing even with randomized returns sequences.

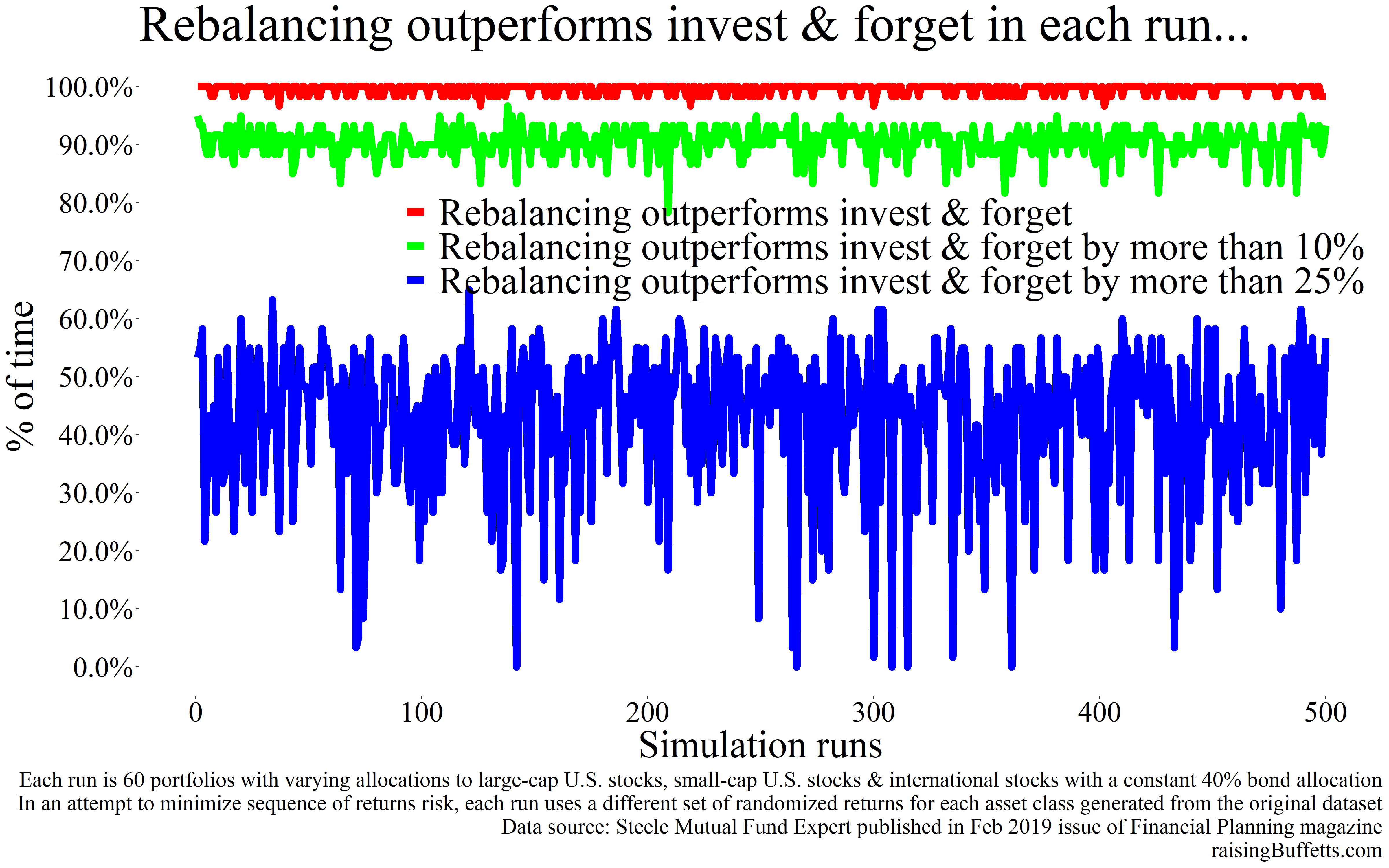

With a 40% constant allocation to U.S. bonds and the allocation to stocks allowed to vary…

Rebalancing wins here as well.

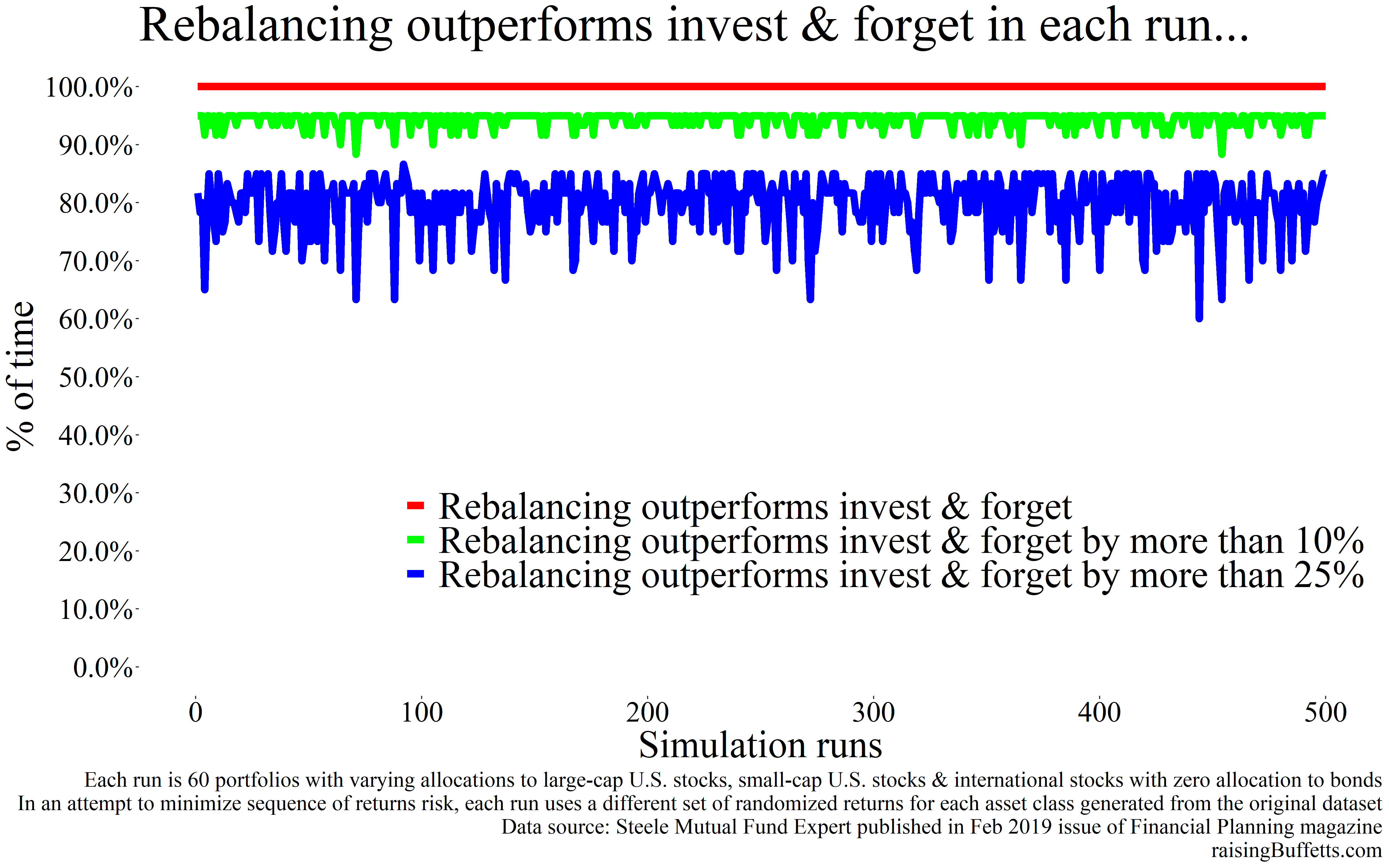

And for the stocks only portfolios (large company U.S. stocks, small company U.S. stocks & international stocks)…

So you’d be crazy to not rebalance your portfolios from time to time.

But here’s a thing. This whole thing is fundamentally based on the fact that mean reversion will always happen. That is, if an investment has deviated from its normal course either on the upside or the downside, it will always revert back to its mean course over the long term.

But what is long term? Ten years, twenty-five years, hundred years? We can only know this in hindsight maybe long after we are dead so that’s one thing to consider.

And what if an investment ceases to exist? Individual companies we know live and die all the time so to guard against that risk, we’d diversify into a sector. Could an entire sector vanish or never, ever revert back to its mean trajectory of growth? Of course.

What about countries? That’s easy, Japan.

The post-war rebuilding which eventually culminated into a real estate led economic boom of the 1980’s Japan was so big and went on for so long that just the fact that it all eventually came crashing down does not quite do enough justice to the sheer scale of that bubble. Edward Chancellor in his book, Devil Take The Hindmost chronicles the reasons for the boom and what led to its eventual implosion.

One of the key drivers for the boom…

Between 1956 and 1986, land prices increased 5,000 percent, while consumer prices merely doubled. During this period, in only one year (1974) did land prices decline. Acting on the belief that land prices would never fall again, Japanese banks provided loans against the collateral of land rather than cash flows.

Land prices will never fall again, wonder where we have heard that before? So the banks lent money just because the value of the land rose. And the more it rose, the more they lent, creating that self-fulfilling feedback loop of ever increasing prices, leveraged to the hilt. Things got so crazy that by 1989,

The grounds of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo were estimated to be worth more than the entire real estate value of California (or Canada, if you preferred).

And the post-crash recovery didn’t quite materialize or hasn’t yet materialized due to structural reasons that are unique to Japan, though there are signs that things might be finally on the mend. But then they have a long way to go.

Back to the rebalancing or not rebalancing question at hand, so if a portfolio design is done not considering the fact that there might not ever be a mean reversion, we are doomed.

And I might have insinuated before that I am strongly in one camp or the other but I am not completely sold on either. So I employ a mix of both. And that’s because I don’t know the future. No one knows the future but try one must with as much supporting research and evidence. And a bit of intuition.

Thank you for reading and persevering through.

Until later.

Cover image credit – Matthew T Rader, Pexels