Phil Knight, the founder of Nike writes in his book Shoe Dog about how incredibly difficult it was to raise capital to fund his then fledgling startup that went on to become the business it is today.

Venture capital as a funding model didn’t exist back then. And back then is 1960s. You needed capital to start your business? You’d rely on the faith and generosity of friends and families or you’d go down to your local bank to pitch them on the promise that was your startup.

And banks were and still are in the business of lending. They lend instead of taking a stake in your business. So a completely different business model.

And conservativeness is the name of the game. Return of capital is more important to them than a return on capital. An excerpt from that book is indicative of those times.

“Here I’d built this dynamic company, from nothing, and by all measures it was a beast – sales doubling every year, like clockwork – and this was the thanks I got? Two bankers treating me like deadbeat?”

Phil Knight in Shoe Dog

So imagine where we would be if we had to rely on capital from banks to fund our bleeding edge businesses of today.

But then we also have the landscape of today. Apoorva Dutt wrote a piece that is based off of excerpts from Dan Lyons book titled Lab Rats which talks about how Silicon Valley’s business model of moving fast and breaking things is making life miserable for the rest of us. This was in 2018 and things have just gotten crazier since then. Some choicest excerpts from her piece about Dan Lyon’s book…

“Silicon Valley has no fountain of youth. Unicorns do not possess any secret management wisdom. Most startups are terribly managed, half-assed outfits run by buffoons and bozos and frat boys, and funded by amoral investors who are only hoping to flip the company into the public markets and make a quick buck. They have no operations expertise, no special insight into organizational behavior. All they have is a not-very-innovative business model: they sell dollar bills for 75 cents and take credit for how fast they’re growing.”

Apoorva Dutt, Tech in Asia

“The vast majority of these new companies are losing money. Traditionally, to get rich in business you had to build a company that turned a profit, and then the profits were shared with investors. The new VCs have invented a form of alchemy in which they make a fortune for themselves while skipping the step about building a profitable company. I call it, Grow fast, lose money, go public, cash out. You pump millions (or billions) into a startup, so that it grows rapidly. You generate hype, flog the shares to mom-and-pop investors in an IPO, and scoot away with the loot. In 2017, I made a list of 60 tech companies that had gone public since 2011. Fifty of them had never made a profit. Some new companies lose incredible amounts of money.”

Apoorva Dutt, Tech in Asia

That’s harsh but there is also truth in that. And we can see some of that play out lately with many of the newly listed companies with their values down 50 percent and more. And they are still nowhere from being reasonably priced.

Venture capital as an ecosystem is not designed to work with a lot of capital. In fact you make things worse for startups who are doing things right and playing by the books on their plans to grow a business with profits as the end goal. And that must be the end goal for the system to flourish.

Because you can always throw junk in the public markets and the public might lap it up. To a point. It’s that same fool me once, shame on you, fool me twice, shame on me endgame.

And we don’t want that endgame.

Of course, few businesses start out of the gate being profitable. But there must be a point beyond which profitability becomes imperative. We cannot have billion dollar businesses perpetually losing money.

Mihir Desai, professor of finance at Harvard Business School and an author of one of my favorite books, The Wisdom of Finance, wrote a piece in New York Times right before Uber was about to go public and why you should root for that IPO to fail. That’s cruel but hear him out.

“This cycle – in which unsustainable start-ups make ever-larger promises to bloated venture capitalists, who promise more than they can deliver to flush sovereign wealth funds, who are too eager to believe them – distorts the allocation of capital and talent. The rush to invest, no matter the underlying economics, diverts entrepreneurial energy toward unviable business models.”

Mihir Desai, New York Times

Of course that’s nothing to do with Uber but that’s what we get when so much capital is chasing returns wherever it can find in this ultra-low interest rate environment with pension funds, endowments and even John Q public piling in.

Now that I’d depressed you enough, there’s still a decent justification for you to still participate in this ecosystem because not many avenues exist that can add sparkle to your portfolio with returns beyond what you already have access to. Plus all that thing about backing entrepreneurs and helping turn their dreams into a viable product or a service.

So how do you decide how much can you afford to invest in this space?

I’d start with my 10 percent rule. That’s your play money and venturing into venture capital is equivalent to that. Very high risk with a potential to knock it out of the park.

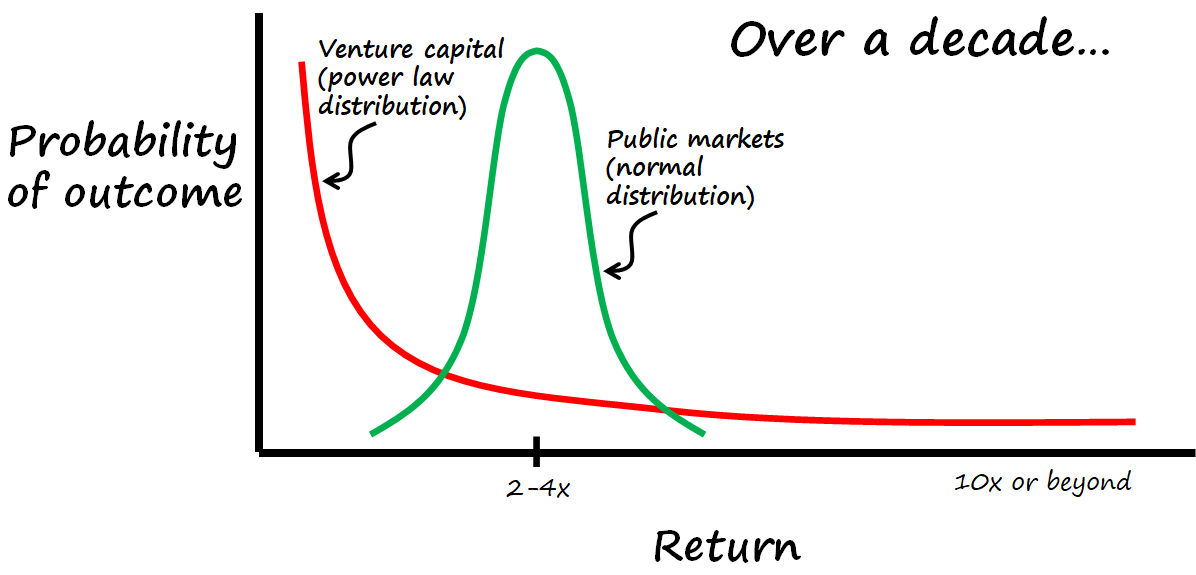

For those that are into statistics, traditional stock and bond investing have returns that are more normally distributed. Venture capital returns follow a power-law distribution.

And data shows that you’ll need a minimum of 50 investments to even have a shot at this.

So assuming you deploy $10,000 in each one of them, that’s $500,000 right there.

But you can’t just invest once and be done with it. You need to invest at the minimum in a follow-on round to make sure you don’t get diluted out of your initial stake.

So that’s another $10,000 for each of those 50 bets.

So you need to carve out a million dollars from your portfolio to play this game. And since this can’t exceed 10 percent of all the money you have means you can only afford to play this game if your net worth is in the 10 million dollar range.

So that’s the hard math.

The way around it is to invest in a pool with other like-minded investors. That way, you can get exposure to this asset class even with a lot less.

To me, investing in this sphere if opportunity presents itself is to be an enabler of this ecosystem. Not that it needs any of mine or yours help in the current environment.

But if there is a chance to strike it big, there is also a chance it all flames out. That’s the nature of this game and you must play the game to find out.

Thank you for reading.

Cover image credit – Startup Stock Photos, Pexels