What is money? Yes, we know how we make it and spend it but that’s not its only utility. Money is stored energy. It buys us options. You might love going to work today but abruptly things change. Like say your company gets acquired and they now deem you redundant. Suddenly you are out of work. Or say your work environment takes a turn for the worse. Imagine all that stress and anxiety that comes about due to situations that you had no control over.

Money gets you that control. It puts you in the driver’s seat. It gives you that ability to dictate how you want to spend your time, with whom you want to spend that time and for how long. Not only does it buy you options, it also buys you freedom.

And that path to freedom starts with savings first. You have to set money aside, whatever the amount, to get to a point that first takes care of emergencies. Like a car breaking down, an unexpected medical expense or in the worst-case situation, a job loss.

So a healthy savings pile is crucial to tide us through such emergencies. And the data shows that we as Americans are failing miserably at this first step towards stability.

Now some of that is not our own doing. Circumstances prevent us from taking this first step because incomes have not kept up with the rise in the cost of living. And that is so unfortunate.

But with that aside, some of it is behavioral as well. Consumerism runs rampant in our society and Americans are the best at that. I mean worst at that. We are expected to spend because our global economy relies upon the fact that when no one consumes, Americans will pick up the slack.

That is sad and we need to reverse that because not only does it wreak havoc with our personal finances, it also destroys our world. Literally.

So we need to not heed that proclamation to spend but instead, save. I say start with setting aside at a minimum six months of living expenses in something that is highly liquid and accessible. Like a bank. And when an expense emergency strikes, you are ready with ammunition to blunt the impact.

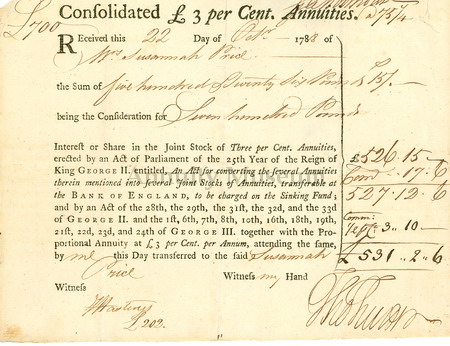

Now liquidity and accessibility has a cost and that cost comes in the form of lower returns. Or interest rates to be more precise. You don’t earn as much on your money because it is designed to not earn as much. As of this writing, we are looking at less than one percent interest rates on bank savings accounts. And that is where this money should reside.

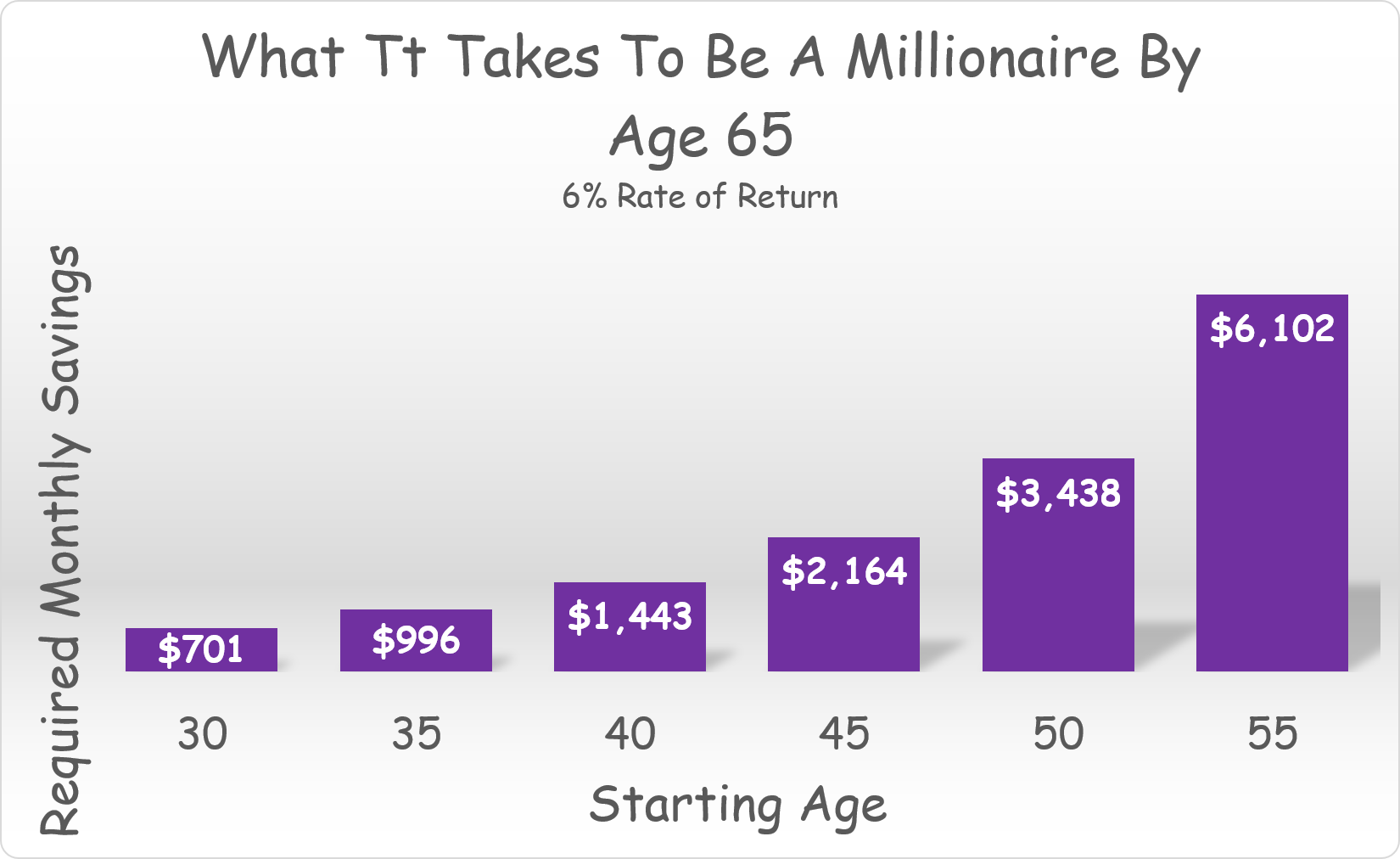

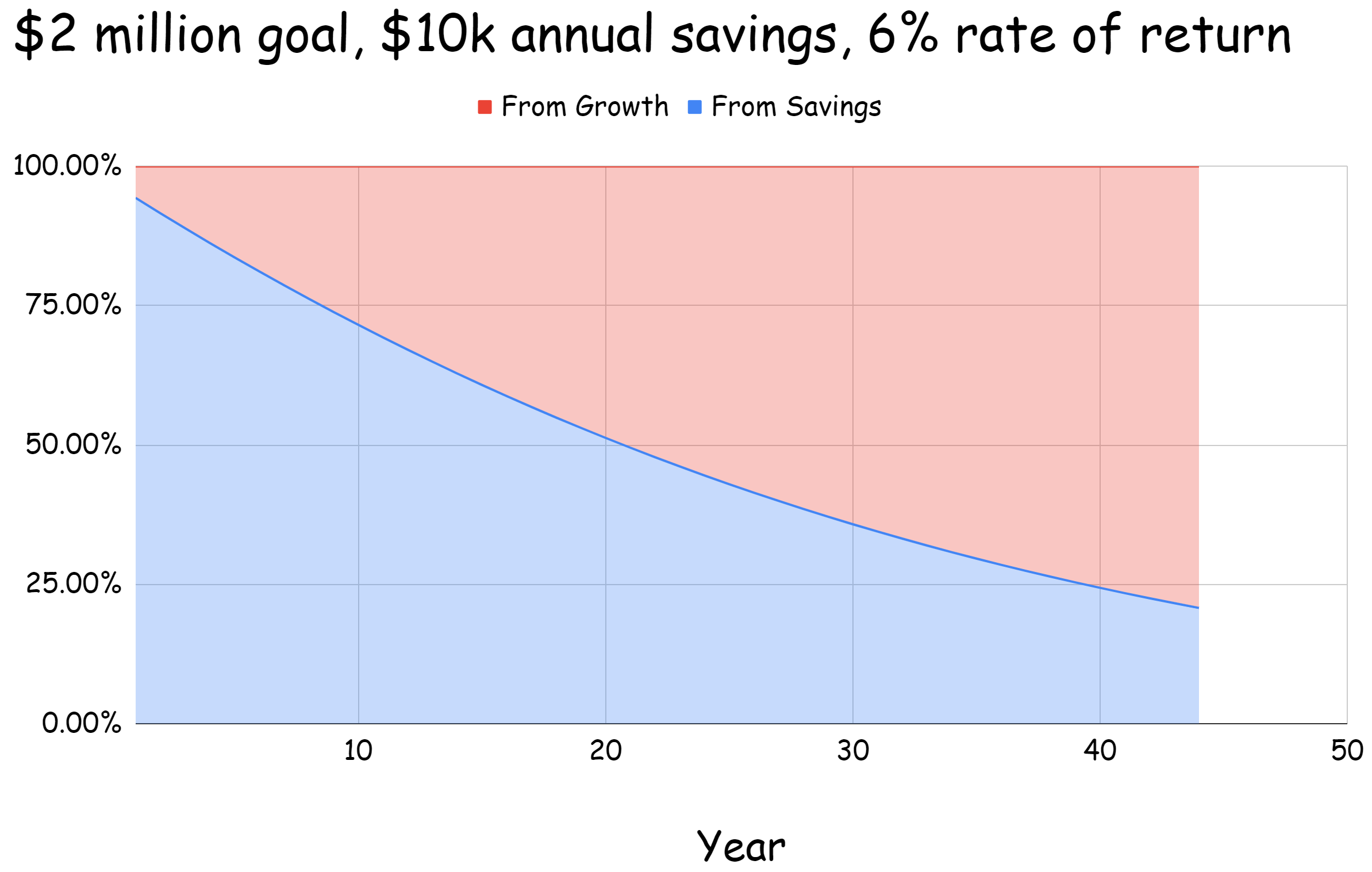

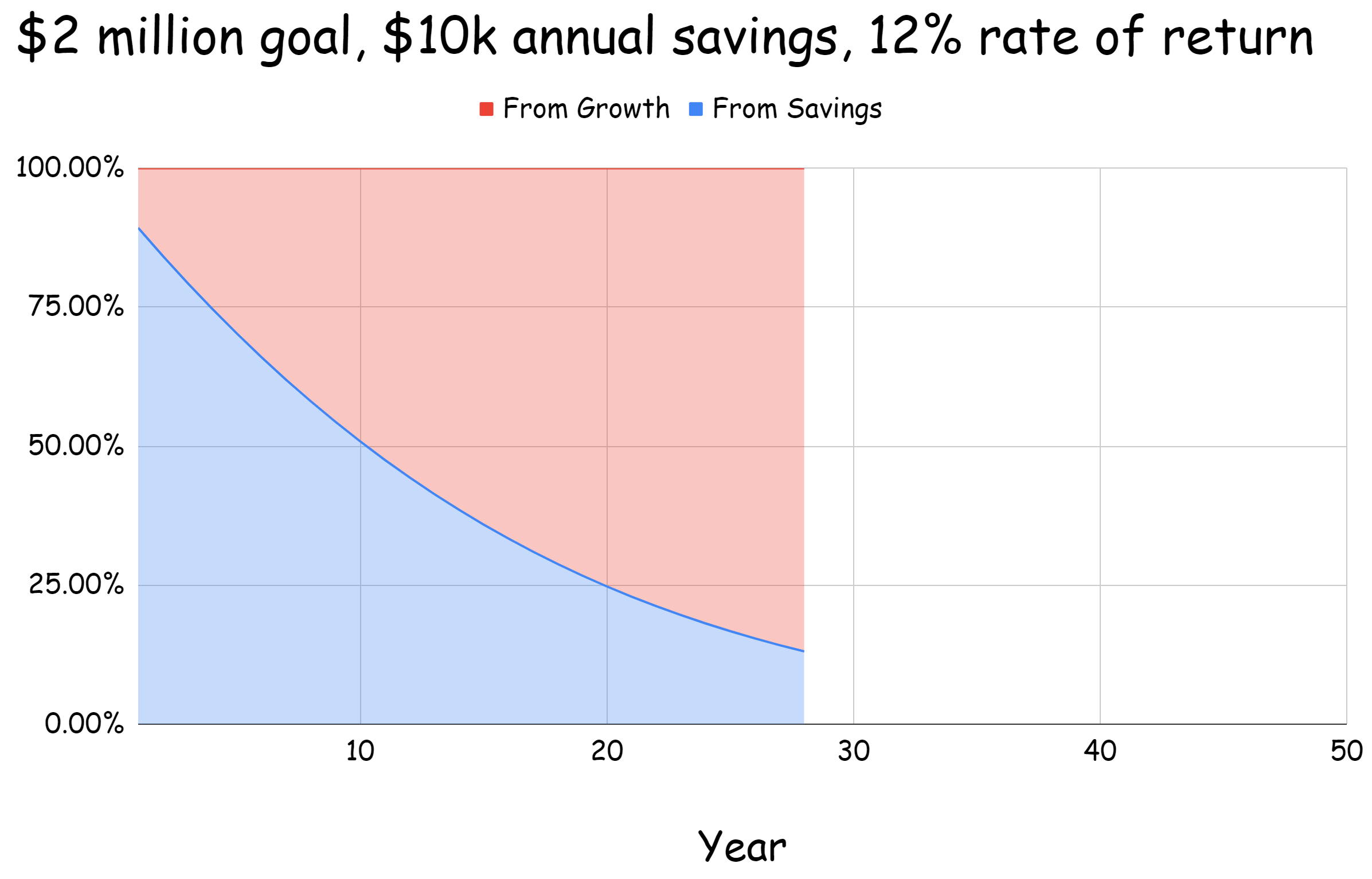

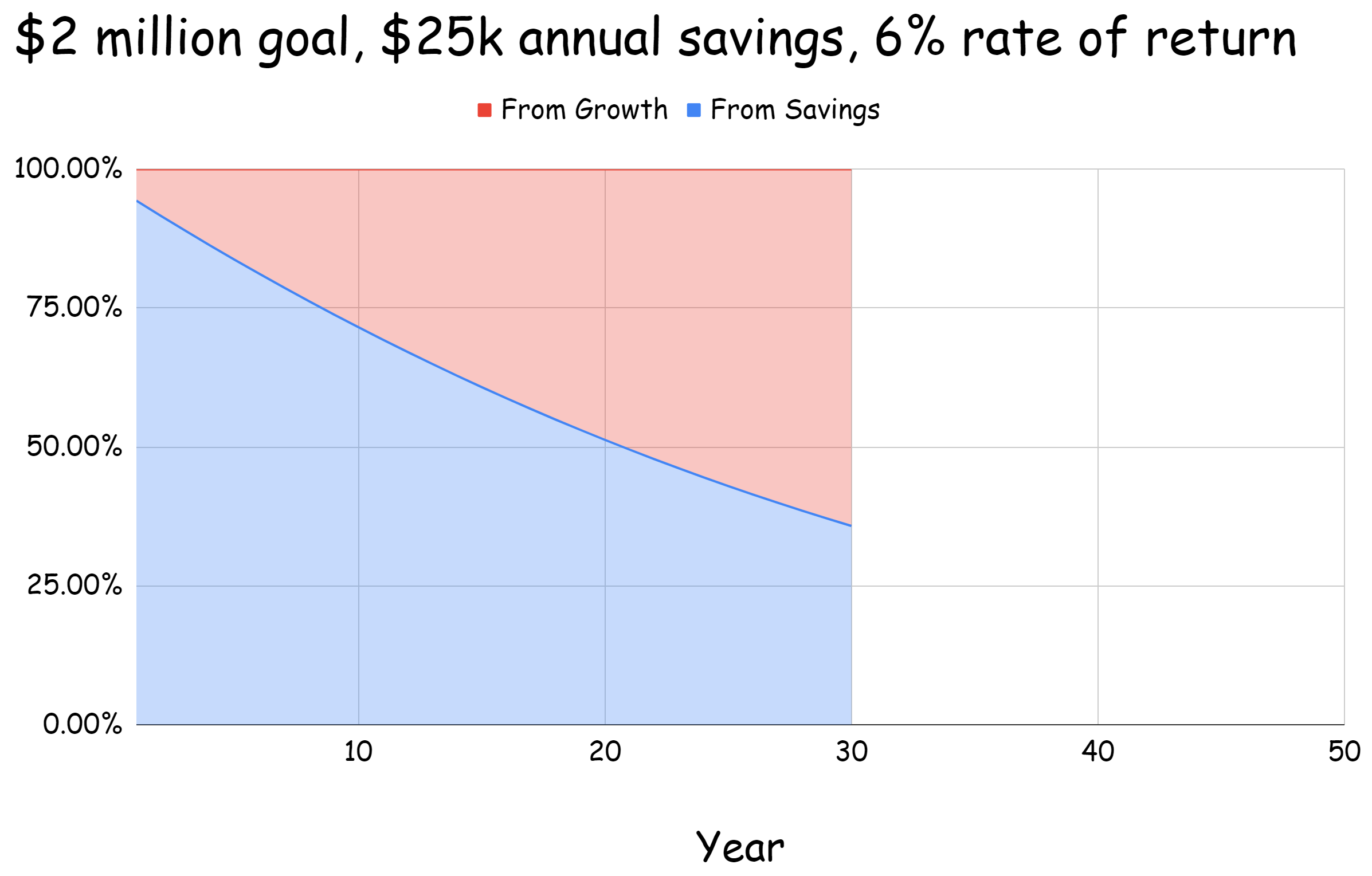

So that’s for the shorter-term goals. But we know we can’t keep stashing our cash in the bank for longer-range goals like say saving for retirement. We need rates of returns that are higher, much, much higher than what a bank account yields.

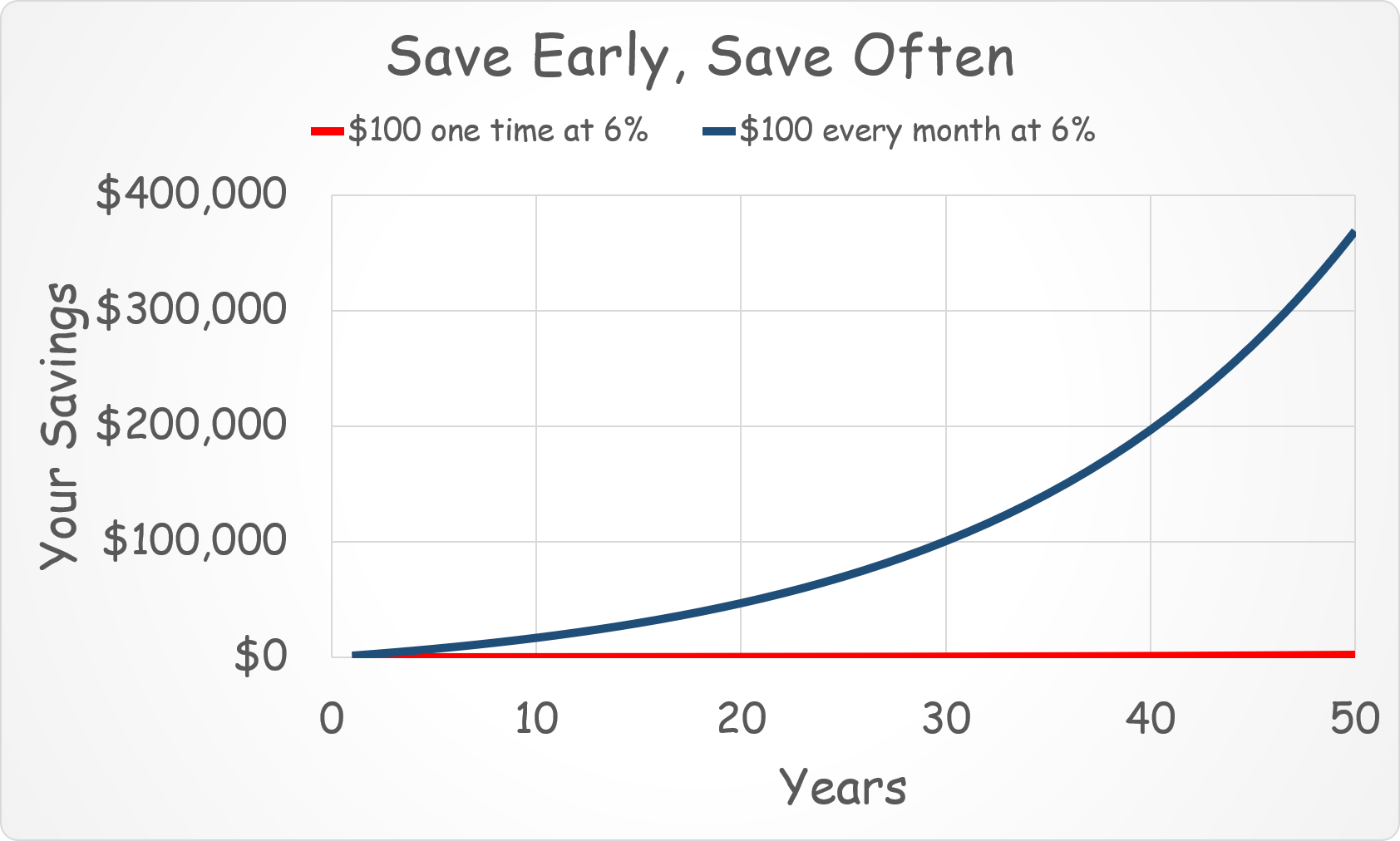

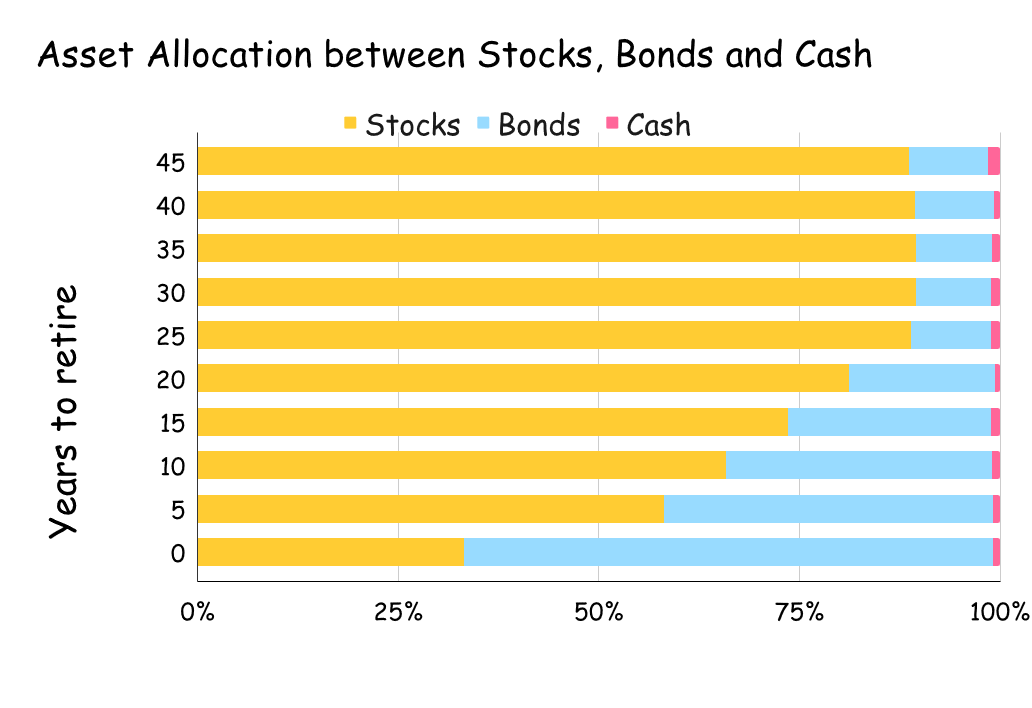

And the only way that is possible is through the process of investing. And investing means risks but the longer one can remain invested, the lower the risks become. One of the easiest ways to invest and participate in our global economy is through the stock markets. Plural because there is not one stock market. There are many. And we need to participate in all of them.

Stocks as we know are ownership stakes in businesses and they have historically delivered a higher rate of return than what a bank account yields. They have to by design. In the long run of course.

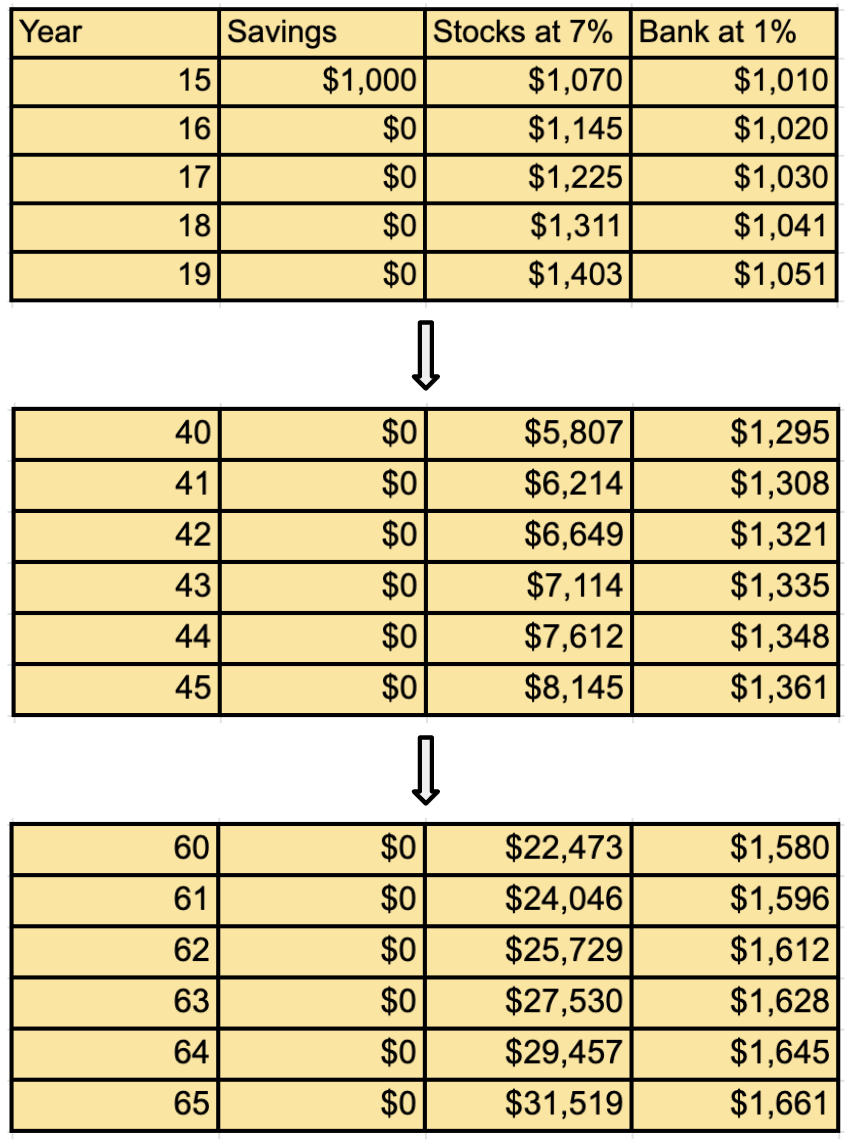

But words are just words. Let’s look at the numbers to see why invest rather than just stash our savings in a bank account. We’ll start first with a single one thousand dollar set aside in these two different vehicles and compare the outcome.

Seven percent for stocks is just about right in the current interest rate environment. It could turn out to be conservative in the long run but as they say, better to be safe than sorry.

So we see the difference.

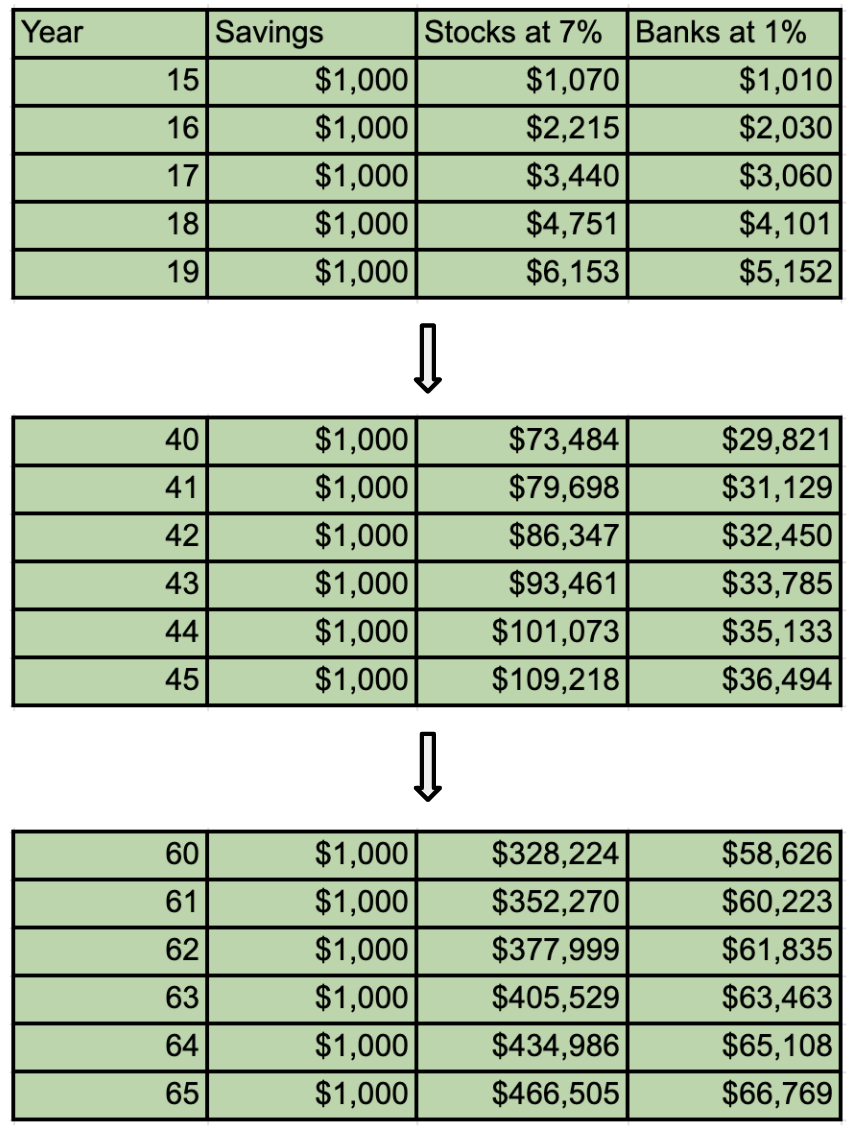

Now a single one thousand dollars of investment is not going to do much. So instead, say we save a thousand dollars each year. And this is what we get…

So much better. But say the amounts even with that are nowhere close to what you need to buy that freedom.

And you realize that pretty late, say when you turn 60.

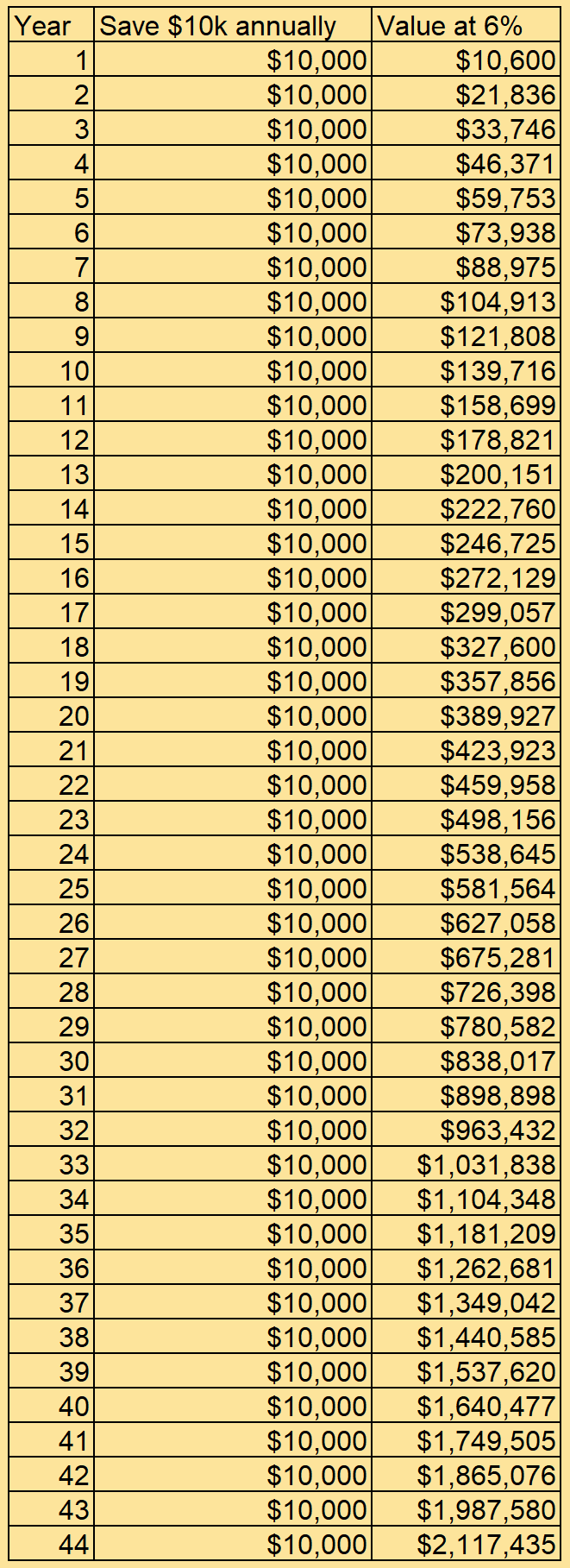

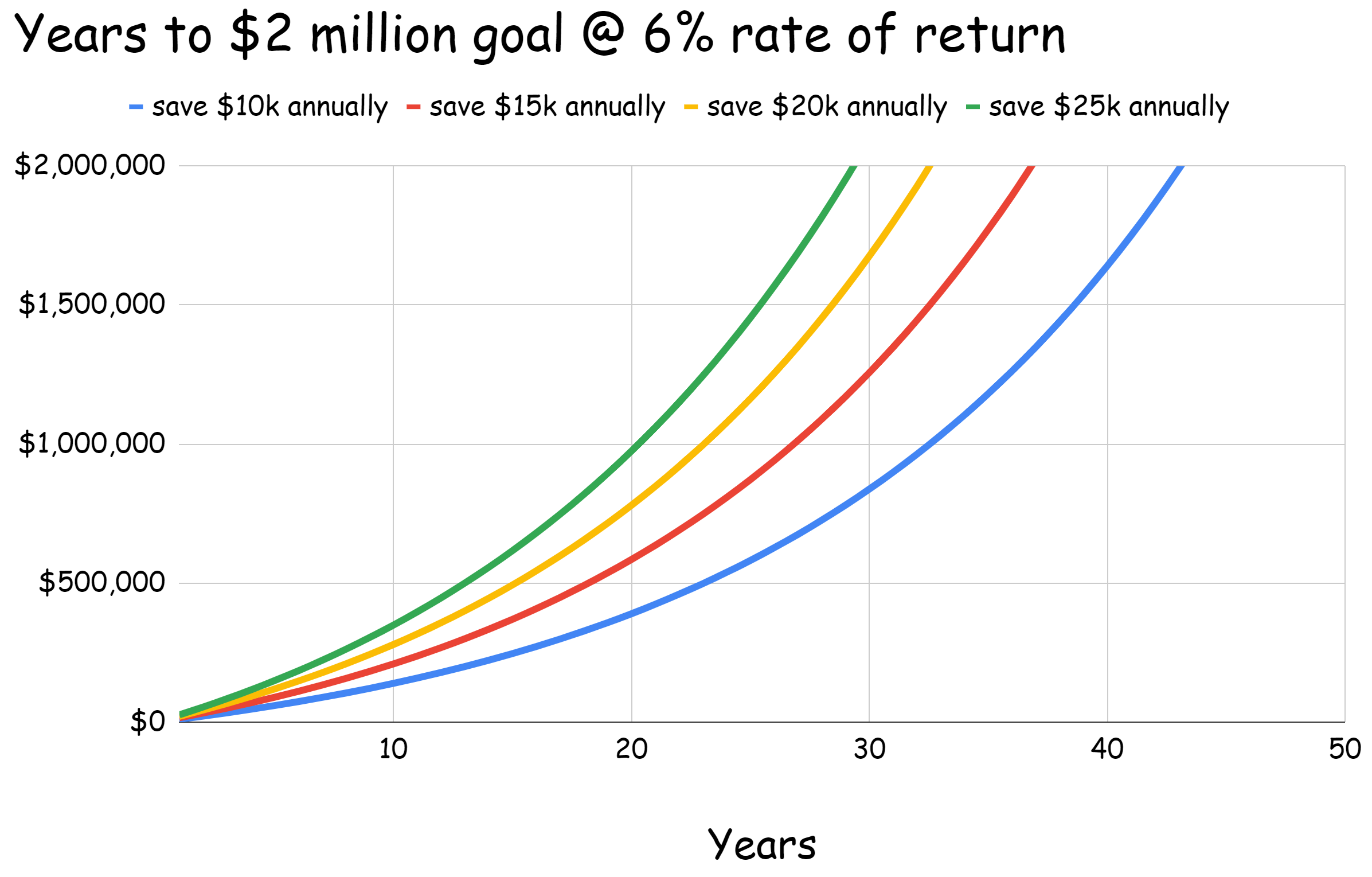

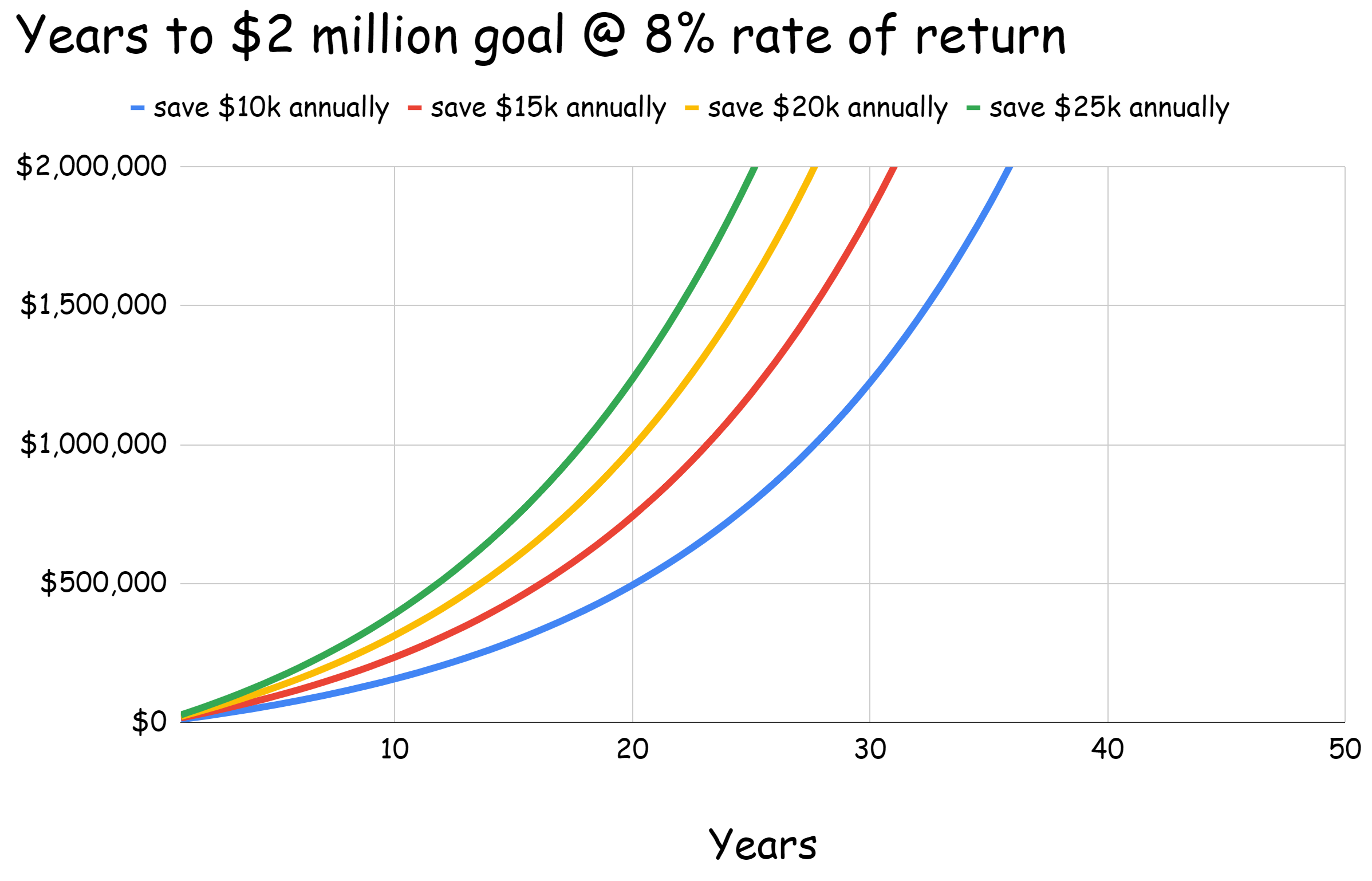

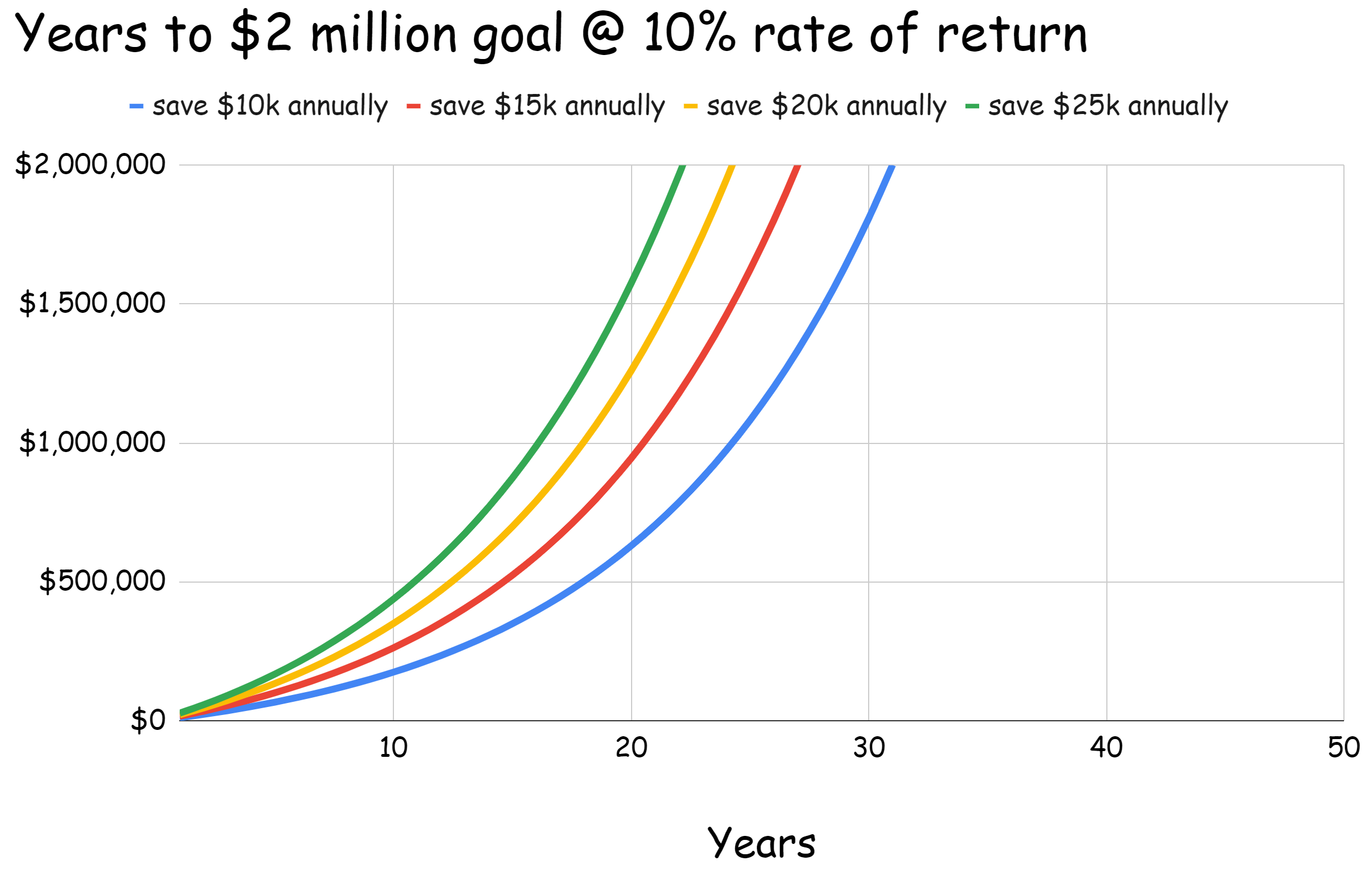

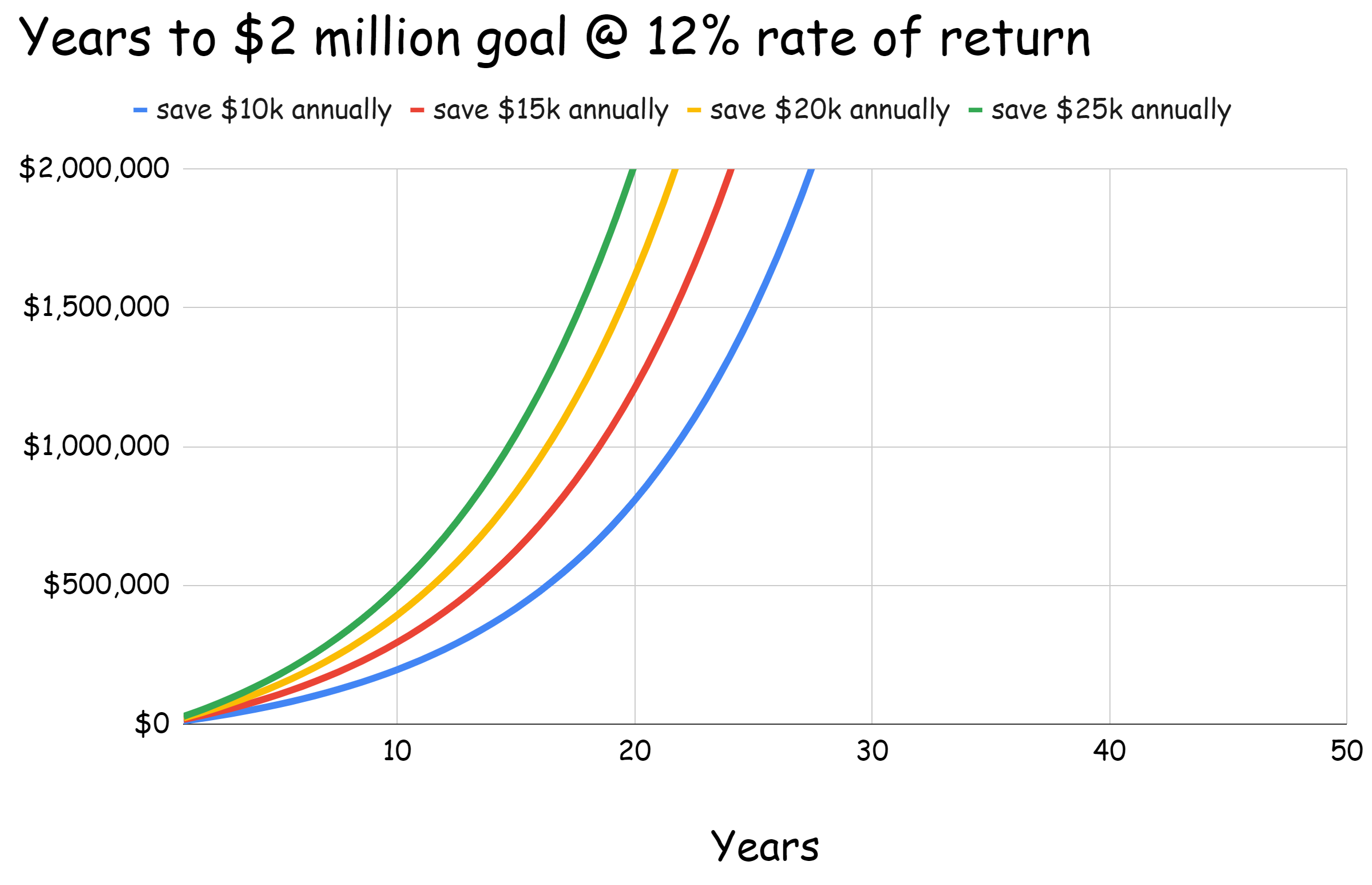

So you try to accelerate the savings amount by doing 10x or $10,000 a year for the remaining years. What do we get?

So there is a difference but not as big as you would have expected. And that’s because your contributions did not have as many years to compound.

But what if you realized sooner and could do the same acceleration of saving $10,000 when you turned 40. And you did it for that same 5 years.

A big difference.

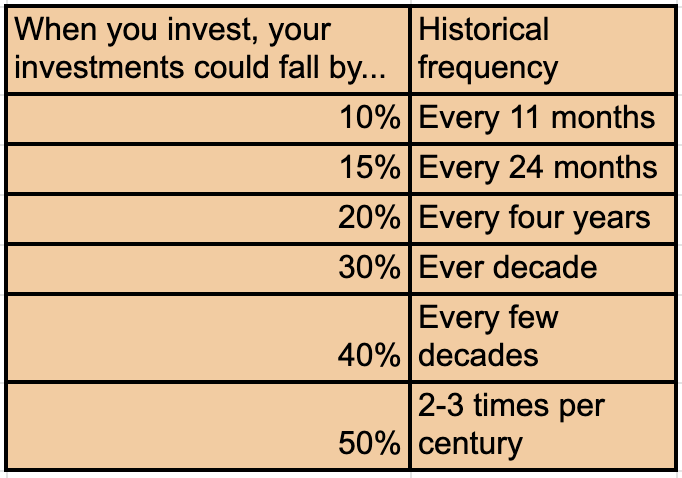

And those stock market returns are not going to come easy and this is how bad it could get every now and then.

At least, that’s how bad it has been historically. So expect that but keep on investing.

In parting, a few things:

- Emergency reserves are a must. Six months living expense is the right amount. And this money needs to be liquid and readily accessible.

- And we can’t rely on ‘safe’ investments to meet our long range goals. That money needs to be invested. But that also means small and big declines in the value of your portfolio every now and then. Be ready and willing to endure through those times.

- And Captain Obvious, the sooner we get our savings into investments, the faster we can buy our way to freedom. Not freedom from work but freedom from working on somebody else’s terms.

That’s all I have to say for now.

Thank you for reading.

Cover image credit – Karolina Grabowska, Pexels