With most consumer decisions, given a choice between two comparable products, the decision to buy one over the other almost always comes down to price. Most buy the one that’s cheaper. Or when things get cheaper.

But this apparently normal behavior somehow escapes the process of purchasing financial assets. And hence, an entire field of finance devoted to trying to understand why investors act the way they do while exhibiting perfectly rational behavior in other walks of life.

But I think investors behave the way they do because most fail to make a connection between buying say a box of Tide detergent versus buying shares in Procter & Gamble that makes that detergent.

And if we dig deep enough with anything we do or consume in our daily lives, there is always somewhere a connection between a product or a service and a business that delivers that product or a service. And that business, if publicly-traded, we can also own a piece of.

My younger daughter is all things LEGOs these days. I mean she spends hours building things like these…

And her gang is into it as well so we know she is not alone.

So then the discussion as usual leads to buying a piece of the LEGO making business. But she can’t because LEGO does not trade publicly.

But then that plastic that makes those LEGOs could be coming from a publicly-traded business. Or that oil that was dug up to make that plastic had to have a publicly-traded entity behind it. And so would the businesses that make those machines to injection mold these pieces or that steel that was used to make those machines or those semiconductor chips that control those machines and on and on.

So if she owned a diversified basket of global stocks, somewhere, somehow, she owns a piece of the supply chain that went into making those LEGO pieces. So she is all squared then.

Talk about supply chain, if you never came across this Milton Friedman video, well, you did now.

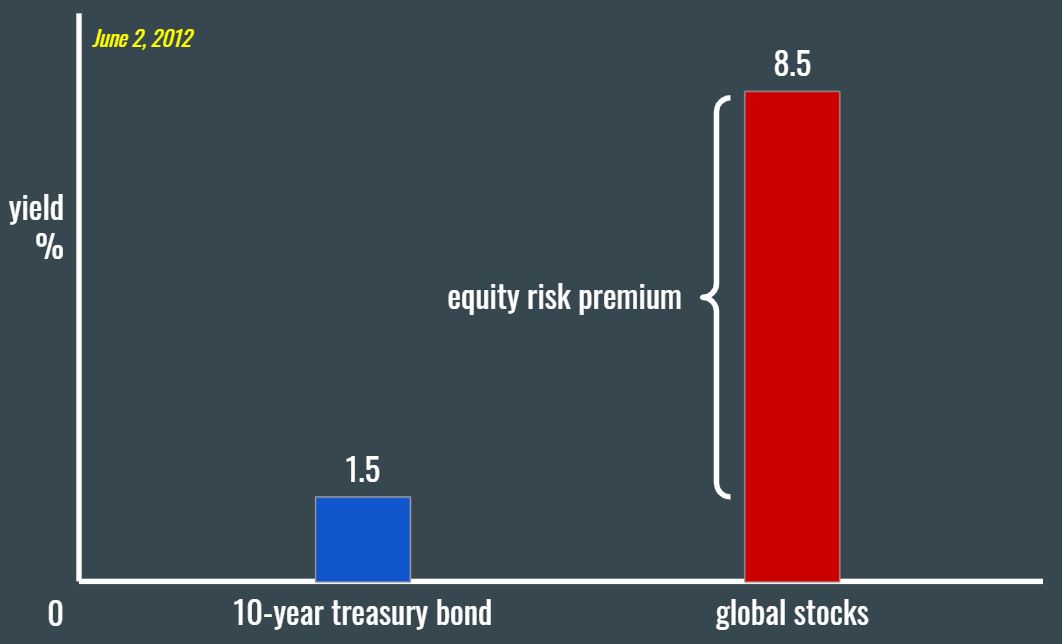

So the other day, I dug up some old notes and this one dates back to June 2nd of 2012. And that scribbling was all about yields – bond yields vs. earnings yield for a portfolio of global stocks. Earnings yield by the way is the inverse of price to earnings ratio.

So the 10-year Treasury bond yielded 1.5 percent at the time when global stocks were yielding 8.5 percent (price to earnings ratio of about 12). Global stocks here refers to the FTSE Global All Cap Index.

Stocks were a bargain then. How sweet of a bargain? The last time the spread was as wide was all the way back in 1962.

And yet investors were dumping stocks left and right, for some reason or the other and at the time, that reason appeared to be the Eurozone debt crisis. In just the April of that year (2012), U.S. investors sold a net total of 20 billion dollars worth of stocks. In May, they withdrew 26 billion dollars from the stock market.

All in all since 2007, investors withdrew some 530 billion dollars out of stocks and stock-type investments.

And where did most of that money go? Into the apparent safety of bank savings account and into bonds.

But that at the time could be considered as a reasonable behavior. Not right, not logical but reasonable. Investors were terrified of the slightest of turbulence. The trauma of the Great Recession was fresh in everyone’s mind.

And hence the equity risk premium. Stocks are risky because profits are not guaranteed. But if there was no risk, the earnings yield for stocks would collapse to meet that of bonds.

But earnings or profits for businesses can and do fall. And that causes the value of these businesses and hence the stock prices to fall. So the risk.

But in hindsight, that was THE time to plow everything you had into the markets.

And what was predicted at the time to be a great time to invest was indeed a great time to invest. I mean if you were anywhere close to the stock markets this past decade, you made money.

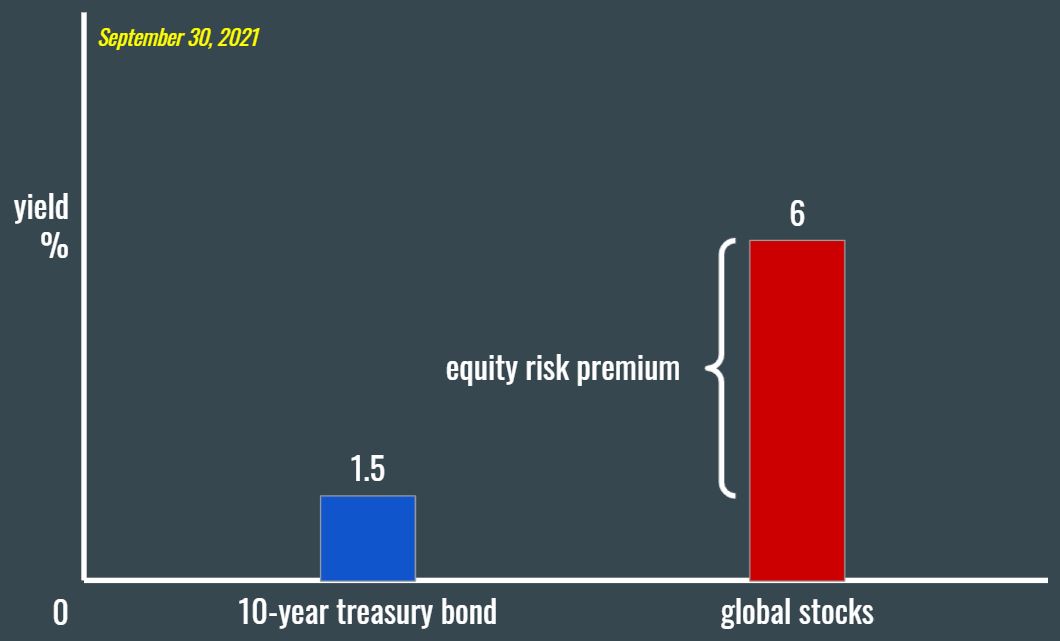

So where are we now? The bond yields are about the same but the earnings yield for stocks have basically cratered. That is, the equity risk premium got reduced.

And most of that reduction in the equity risk premium happened because of the expansion in multiples. I mean you were paying 12 times earnings for a portfolio of global stocks in 2012. Now you are paying 17 times that.

But then it sort of makes sense. Besides that small hiccup at the onset of COVID, we have basically forgotten what risk is. The Great Recession is a distant memory. The Dot-com crash of the early 2000s is like it never happened.

And hence the complacency.

What do I personally wish? I wish for a renormalization of interest rates. That’s assuming we know what “normal” is in the interest rate world. Maybe we are in a new era and maybe we never go back to the way things were but I think we must considering all the craziness that is out there in the markets these days.

I want things to reset a bit. I want the bond yields to grow and the equity risk premium to expand back up. So technically a double hit on the price of stocks.

Painful yes, in the short run but ideal for most of us in the long run. We rather take the medicine now than having to surgically remove a tumor later. Bubbles are painful when they deflate.

So if you are a millennial or a Gen Xer, you should get down on your knees and pray for a decade of flat returns. That’ll allow you to pump as much powder as possible into the markets while the bond yields normalize and the equity risk premium reflates.

None of it says that you sell your stocks. Because no one knows the future and you don’t want to get into the game of predicting the future. But if you’ve got a reasonable plan and a decent portfolio that fits that plan, you can tweak and make adjustments to that portfolio where and when necessary but you must stick to that plan.

That of course requires conviction and conviction only comes with knowing what you own is what you should own but once that’s done, all you can and all you should do is throw as much savings as possible into that plan and wait.

Thank you for reading.

Cover image credit – Tran Long, Pexels